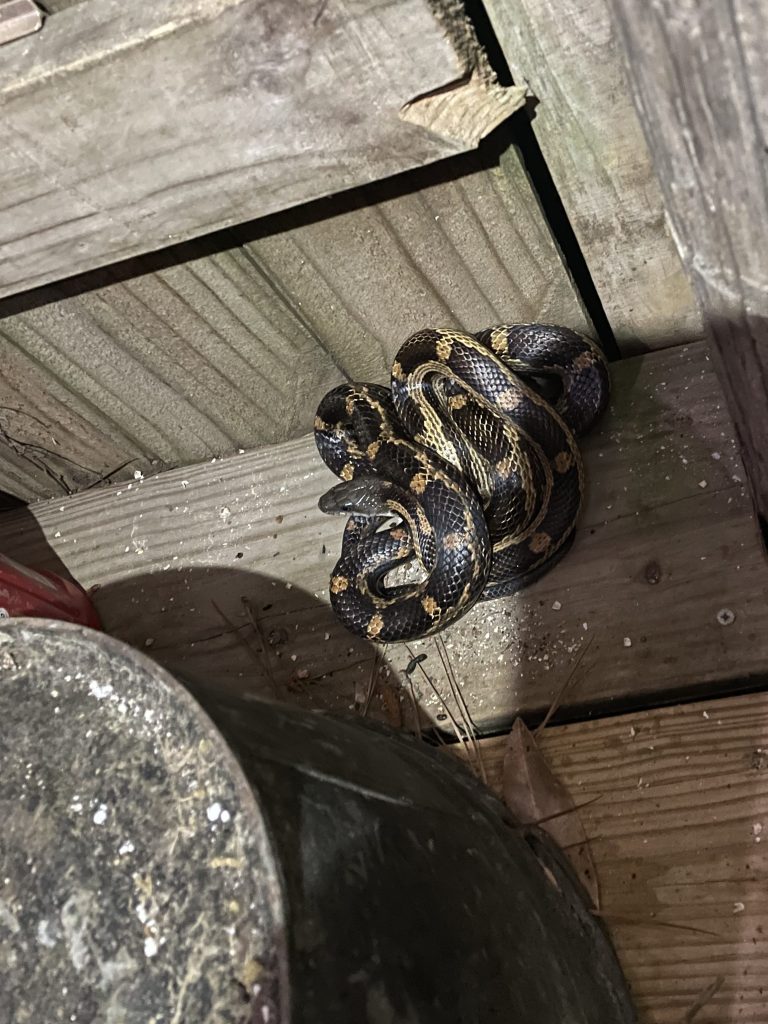

In the blackness of night and after two gin and tonics, the snake in the shower didn’t look so scary. There I stood, wrapped in an oversized beach towel, bare feet covered only by thin leather flip flops, staring at the mottled black and tan reptile resting under the twinkle lights and just above the 32 ounce bottle of Dr. Bronner’s castile soap. Stretched from wall to wall, he was easily four feet or more. At first glance, I thought it was a joke – a plastic relic from last month’s medical students who use these woods as a classroom for wilderness medicine. Lynn stood at the shower’s outer wall, his hand on the knob of the tankless water heater, ready to adjust the temperature. My encounter with the snake was brief, lasting only long enough to register its presence. I dropped the green canvas curtain, slowly backing away.

“Are you going to do something about that snake in the shower?” I calmly asked.

“What snake?” Lynn answered, moving toward the shower’s entrance.

“The one draped across the back wall.”

“I didn’t even notice him. Grab a phone, we’ll take a picture.”

For a photo snapped with only a few twinkling LEDs for light, it’s not a bad pic. Although by the time Lynn took it, with me peering over his shoulder, the fearful snake had coiled itself into a spaghetti-like knot in the corner. After its photography session, with some nudging from Lynn and a metal bucket, the serpent slithered down a sturdy post, seeking cover in the longleaf pine needles blanketing the forest floor.

The next morning, a photo comparison to the 1979 edition of the “National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians” revealed our cold-blooded friend was a Elaphe obsoleta, or as most of us know it, a common rat snake. In all likelihood, it’s the same one, although older and larger, Lynn found in the tool room adjacent to the shower. It’s worn skin, shed in a growth spurt, fills an antique mason jar and sits next to a clay face jug warding off evil spirits from the camp bookshelf. And possibly this is the very serpent who, one steamy July day, caught the humid breeze from the rafters of the dogtrot porch while my sister-in-law, a woman fearful of all slithering and crawling creatures, unknowingly trod again and again, beneath its reptilian presence.

Like much of the wildlife on our land, the rat snake is safe here. This is a fine ethical line we walk, as invasive feral hogs with their destructive ways and prolific reproduction rates are unwelcome anywhere on the property. And carpenter bees, which attract pileated woodpeckers, long ago lost their invitation to party at the camp house. But the rat snake is a long powerful constrictor, and a skillful climber, who eats birds, eggs, mice, and other small mammals. While I prefer it stay away from the birds and their eggs, this creature is nature’s rodent control. It’s a beneficial player in keeping the ecosystem in balance.

It’s normal to fear what we don’t know. And for many people, protecting a snake, harmless or otherwise, is counterintuitive. In Meditations from the Mat, yoga teacher Rolf Gates writes about the power of training the mind and how “confronting our fear helps to broaden our perspective.” If we see the rat snake for the role it plays in nature rather than rely on our preconceived notions to fear it, we see it through a wider lens. Letting it go to live out its life, is a better choice than harming it.

This idea, as it applies to society, wasn’t lost on me when I read the local news recently. A private organization held a drag brunch and fundraiser at our town’s civic center. It was a PRIDE month celebration by a non-profit organization who lawfully rented the space. News headlines hyped it as a notable event in conservative coastal Alabama. The news also pointed out a handful of residents opposed the event. Pictures show five protesters on a public sidewalk outside the civic center, carrying crosses and signs reading, “protect childhood innocence.” Only adults were permitted to enter the auditorium. It seems, like those who want to harm a snake, these individuals were driven by fear of predetermined ideas. If I had to guess, the protestors had never met or had a conversation with the drag brunch organizers or entertainers. It’s a safe bet they had never bothered to ask them about their day jobs or contributions to society. If they gathered in a coffee shop or a bar, without labels and preconceived notions, would they look one another in the eye, discovering they had things in common. Maybe and maybe not. But it would be a start.

In this time, with war raging on two continents and the widening gap between left and right in our country and others, it feels more important than ever to step back and examine our fears – be they of people or reptiles. Difficult discussions and acknowledgements that things aren’t always as they appear, broaden our perspectives. The rat snake is a simple reminder that sometimes beings aren’t as scary as we believe. I’m not saying I want to share the shower with a snake (and drag queens don’t have to share the auditorium with the religious right) but knowledge and tolerance of one another help us confront our fears. The snake can stay. I’ll take the shower. It can claim the toolroom, the rafters, and all the mice it can eat. Every now and then we’ll meet and acknowledge our roles in balancing rather than harming this ecosystem.